The Invisible War: Life after a Traumatic Brain Injury

Throughout my career in the Marine Corps, beginning with my first deployment, I was exposed to blast exposures without any knowledge of how they could affect me. From wall charges to satchels of C4, grenades, and tanks, getting your bell rung and bones rattled was just part of the job. Many enlisted servicemen and women are too young to think about the invisible damage being done. (Besides, you are wearing a helmet which pretty much makes you invincible.)

Unfortunately, because of that ignorance, and like many others of my peers from that time, I continued to push the limits without knowing how brain damage works.

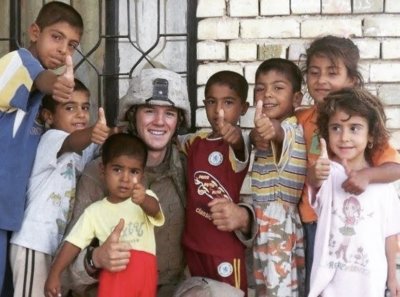

My last deployment was rough, and exposure to blasts was not uncommon. The Marine Corps implemented a 3-strike rule for anyone who had three experiences of unconsciousness, diminished cognitive abilities or other symptoms from an explosion or blast. You would then be taken from your brothers outside the wire and sent back to the main base. There, you are alone, doing nothing while you wait for your unit to finish the deployment. Of course, loyalty runs deep, and the idea of leaving your brothers was blasphemous. Giving a thumbs up or saying you’re good, became the unspoken rule. No one said a thing unless it was life or death.

When I returned home from that deployment, 3rd Battalion 5th Marines was “bloodied, but unbowed” as W.E. Henly put it in his poem Invictus. My self along with my peers had subtle struggles that we would voice to each other in passing, as if embarrassed of not being able to describe the wounds.

At home, these began to manifest in things such as the desire to sleep from debilitating, insatiable tiredness or lack of desire to participate in any extra activities. Waking up, going to work, and coming home was draining emotionally, mentally, and physically. Once home, I only desired to sit and watch a show or play video games — anything to just escape my mind.

Next began an inability to articulate and formulate thoughts or hold conversations. I became easily confused in conversation, and my ability to recall any information from the conversation was non-existent. Simple tasks such as noticing the trash was full and taking it out or deciding what to eat or what to wear became impossible — not from indecision but a literal mental barrier that meant I was unable to process what I was looking at. I could see my clothes hanging there and know what I wanted to wear, but I would end up staring blankly as if I couldn’t register what my clothes were. My inability to do math, concentrate and focus, study and read, understand and communicate, remember anything short or long term began to dissolve into the abyss of a mind frustrated, scared, and embarrassed with every waking hour and day.

Another aspect of traumatic brain injury is impulsivity. For those fortunate enough to be seen by a professional and be diagnosed with a TBI, one of the first things they will be told is to avoid getting married, making big career or financial decisions. Friends and family would be given the same warning and asked to be observant of their behavior in order to help them.

And this was the case when, much to the surprise of my wife and family, my career in the Marine Corps came to an abrupt close with a back injury, diagnosed PTSD and depressive disorder, along with an undiagnosed TBI. Because of the diagnosis, I began my journey with prescription drugs covering a myriad of symptoms, from stimulants such as Adderall to anti-depressants, on top of muscle relaxers and pain.

Because of my skill set as a scout sniper, I was a highly sought out and desperately needed asset for other government agencies doing diplomatic protective security in austere environments overseas. Despite major aspects of my personality now unrecognizable from my pre-deployment self, I still was capable of executing the professional skills which, by that point, had turned into second nature.

So began my career as a private contractor, and with it, I was once again subjecting myself to blasts and continual exposure to concussive waves. Starting in 2006, after returning home, my marriage began to strain as a result of my behavior, which could be described as mutual frustrations. She became frustrated with me for what should be “normal” responsibilities — trash, laundry, picking up after myself. I became frustrated with my inability to remember to do certain things on top of being too tired to bring myself to take her out, go on walks, socialize or work around the house. This division only grew as my symptoms grew and become increasingly complicated with every child we had.

In 2014 the un-seen and undiagnosed damage from compounding exposure to concussive blasts finally reached its pinnacle resulting in me having to leave contracting. I knew I had become a liability and agreed with management’s decision. I was deeply ashamed, embarrassed and confused as to what was going on with me, and why couldn’t I pull myself together. “What was I going to do now if I can’t do what I love?” I wondered.

I fell into a deep depression, which eventually, compounded with our other frustrations, and resulted in the end of our marriage in 2017.

My final breaking point came at my first experience on the wrong side of law enforcement. I totaled my vehicle and received a felony DUI. The consequence of which were homelessness and living on the street for a month. My saving grace was the rental car my insurance company provided as part of my plan. This meant that I was able to sleep in the car for that period of my life, but my bank account was emptied and without any money to rent an apartment, hotel, buy food or live, I finally reached out to my family and moved in with my parents.

The road to recovery and living again

The road to recovery has been a war on my mind, body, and soul, demanding a will to recover to be greater than my circumstances and my own shame and embarrassment. While living with my parents, I began writing as a way to process and deal with where I was. I also began reading and learning everything I could about TBI’s — and I was blown away. I was angry that no one had told me about TBI’s. I was angry I was just learning all of this after the damage and consequences had taken their toll on my life, mind, family, and those around me.

My writing turned towards openly sharing and telling my story as honestly as possible, while respecting the privacy of my ex-wife and family. Keeping an open mind toward people’s actions in the face of that experience and two suicide attempts, in my opinion, it is better to seek understanding and be kind, empathetic, and pursue peace than be bitter.

When my writing began to take off and resonate with so many others who had been through similar experiences, it gave me a new purpose in life: to help others heal through writing.

In 2019 despite my newfound writing therapy, I became overwhelmed with the consequences and aftermath of my TBI. Once a successful man financially prosperous with a career I loved, a family, able to be in my children’s lives, now living with my parents and unable to rent on my own due to my inability to sustain employment because of my difficult mental and physical recovery process.

I fell into a deep depression, lost 56 pounds, and didn’t leave the house. I would stay in bed for 17-18 hours a day. Eight months went by. I wanted to die.

In what would become my saving grace, I reconnected with an old friend. It was with her constant encouragement and kindness that I began to pull myself from beneath the weight of all I had been going through. After eight months of dating, we decided to make the step and were married on July 6, 2020. Through her encouragement and understanding, I was no longer ashamed of myself or embarrassed, and with her help, I began re-learning how to live and accept certain aspects of life while adapting to others. With a broken leg, you might cast the break, work through some rehabilitation and make a few positive changes in diet and exercise while you’re down — so too we approached my brain. Slowly and carefully, with her help, I took the steps needed to heal.

One of the hardest and most difficult aspects of a TBI is the fact that it is invisible. The general reaction is one of disbelief. Without any physical markers, it gets dismissed as an overreaction. As a result, people with a TBI being labeled as lazy or emotional, “faking it”, being told “it’s just in your head” (an ironic statement), or that “so-and-so came back fine” or “get a hold of yourself.” Empathy never comes because it’s an invisible sickness.

In the aftermath of our nation’s longest period at war, it has become imperative for everyone to become educated and informed on the effects of a TBI. Employers, friends, family, coaches, religious leaders — having these individuals as a strong support system is absolutely vital for the recovery of the millions of military veterans who are living with TBI.

And those who are giving care to a TBI patient also can’t be overlooked. Caring for someone with a TBI can be emotionally, mentally, and physically taxing. When these selfless individuals find themselves burned out, the situation and tensions can become magnified.

Present-day, my wife and I have been happily married for 10 months. We have invested in an intensive coaching program for trauma and abuse integration, in completion becoming a full-time coach for Veterans, EMS, and first responders as well as for their spouses and family members.

Coaching has been the most fulfilling calling in my life. Through TBI recovery mentorship — helping others heal in marriages and relationships while living life fully — I have encouragement for a successful future. Together we can all continue to grow and heal.

22 Jumps involvement

I met Tristan while I was contracting in Afghanistan. As a fellow brother from the Marines, mentoring and encouraging me throughout a difficult time in my life, he quickly became one of my best friends. When he reached out to me with the opportunity to be a part of and support 22 Jumps, I was humbled and honored.

Over the years, Tristan and I kept in touch when we could, but our schedules kept us apart. The opportunity to get together was always met by a scheduling conflict. When he informed me that he was going to be hosting a BASE jumping event in my hometown — and one that supports the development of therapeutics and treatment for TBI — I was overcome with deep joy. It represents yet another milestone in my step towards healing and putting the hardest years of my life behind me. On May 29 at 22 Jumps, Twin Falls, I will proverbially jump into the next chapter of my life with my brother.

One Response

I really wish you would reach out to Cole Howard re: the TBI diagnosis you both have, just to share w/each other would be healing for both if you. His accident was 8/14/21, so he’s lived w/it for 2 years now. His memory is very good but is still dealing w/some cognitive issues like you had mentioned in your blog ie making decisions, following directions, trouble keeping conversations going, etc.

He lives in Palm Desert, CA w/his roommate. He just started working with Voc. Rehab yesterday & sounded excited about finally getting out to do something constructive & meet people vs sitting around watching TV & going out for walks around the nearby soccer fields before it gets too hot out, which has been his life, daily, until this opportunity finally came up.

I would really love it if you could reach out to him, even if it’s just for a short visit to touch base & I know he’d enjoy it as well.

His phone number is 769-794-3333. Evenings before 9 or weekends would probably be best since he just started working 5 hrs/day.

Please consider giving him a call.

And thank you for your service!

Big hugs,

Sherry